Books are asylum

To say that Karina Szczurek finds refuge in books is to understate the matter. Books held her together through dispossession, flight and years of being a refugee. Certain books have travelled with her across three continents and four countries, through languages, and through love and loss.

For a long time, her mornings have begun with books – two to three hours of reading before the day begins. She has written, studied, translated and edited books.

Now she publishes them. The story of her publishing house – which has published a long string of disparate and often unusual books, and has accumulated several prizes in just six years of existence – is also a story of refuge.

Into the precariousness

For years, the publishing industry has contorted, shrunk, panicked, pulled back, baulked, pondered, merged and scrambled. Through the advent of e-readers to severely diminished attention spans, the rising cost of paper and social upheavals, traditional publishing often looks like it’s hanging on, by its fingernails, to the outside of a rollercoaster car.

But some commercial ventures are not driven by spreadsheets, projections and economic context. They are driven by the pure energy of ‘it has to be’. Karavan Press seems to run on that fuel. And the fuel is all inside Karina.

The fifth Mrs Brink

How Karina, after a lifetime of moving, ended up in South Africa is directly linked to the improbable love story of her romance with an icon of South African literature, André Brink. Improbable, because they lived in different countries, because of the 42-year age gap, and because Brink had been married four times before.

They met when she was charged with accompanying him during a literary festival in Europe. Their conversation started on the ride from the airport. It ended a decade later when André died. She wrote about their love in her book The Fifth Mrs Brink.

In 2025, she will have been in South Africa for twenty years, the longest she has stayed anywhere. Her parents escaped Communist Poland when she was young and they spent years as refugees in Austria and other places.

‘South Africa is 100% home. I completely feel like I belong here. I felt it uncannily from the moment I arrived here. It was such a strong feeling and I didn’t understand it for a very, very long time. But I had an inkling that it was because all the places I lived felt monocultural, monolingual. South Africa was the first place where people were exactly like me for different reasons: whether they wanted to or not, they had to negotiate multicultural and multilingual spaces. Everyone is somehow marked by that. It’s incredibly character-building, whether you resist it or not. It changes you and makes you different in the world.

‘For the first time, I felt like I didn’t have to explain myself to people because everybody was like me – not exactly like me, yet like me.’

The Karavan of refuge

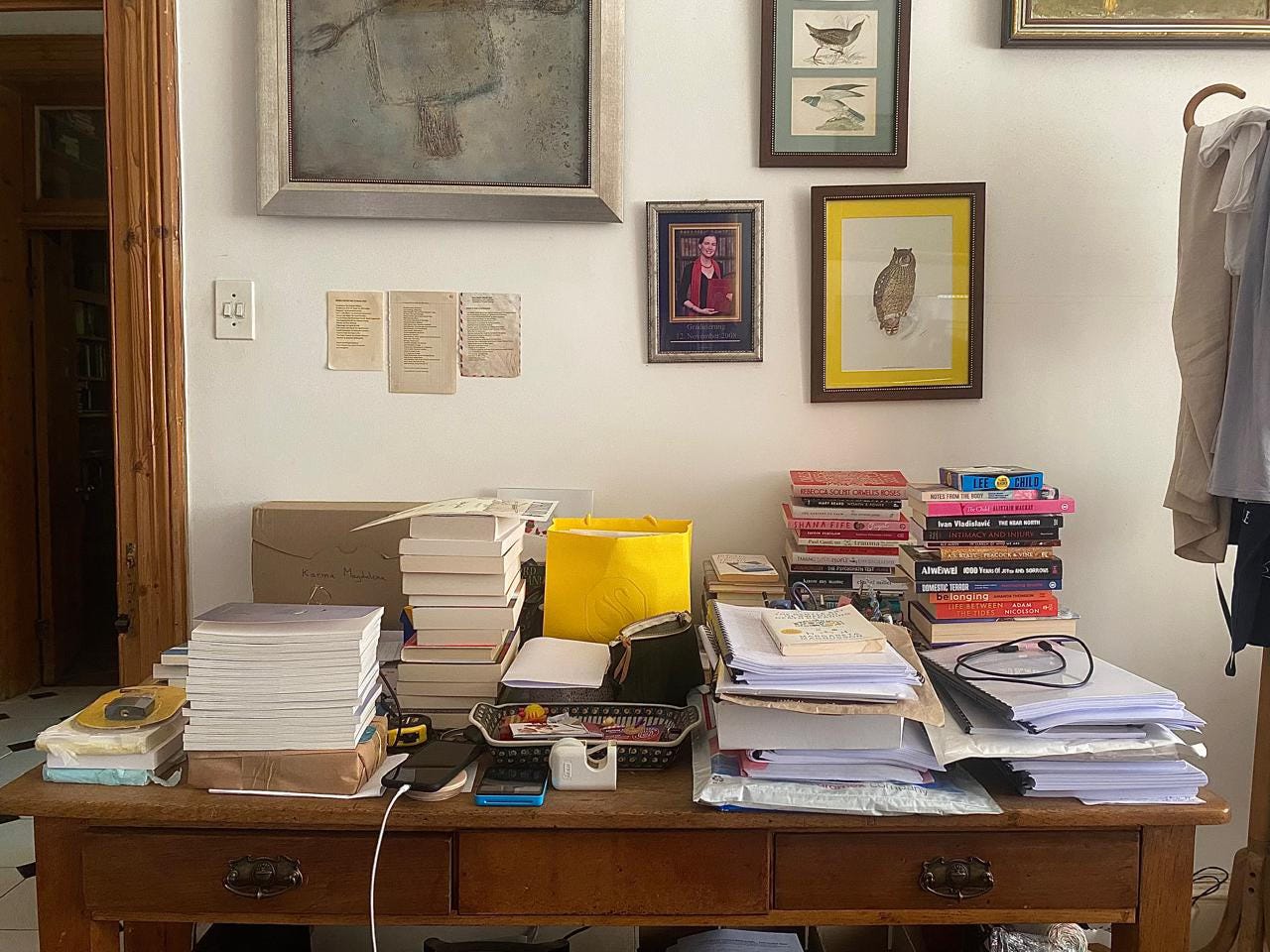

The idea of home is tightly bound up in the name of the publishing house Karina started in 2019. The house she and her books moved into when she came to live here was André’s. The library that sprawled over several rooms contained ‘somewhere between of 15 000 and 18 000’ books.

Then, out of the blue, the couple ran into severe financial problems that threatened their home. This was devastating for Karina. She’d believed she could finally settle.

The way she calmed and consoled herself was to imagine how to make a home she could never lose. She imagined a caravan. She imagined that even if she had to leave South Africa for some reason, she could ship the caravan wherever she went.

The disaster did not come to pass, and ten years after André’s death, Karina still lives in the old Victorian surrounded by a wild garden and propped up inside by thousands of books.

The concept of a ‘forever home’, of a ‘refuge’, also pushed forward the idea for a publishing ‘house’.

‘Working in and around the publishing industry for so many years, I felt that there was a gap here and overseas for a certain kind of book. I felt that publishing was often driven by the wrong approach.

‘Look, I understand of course, that when you have overheads and offices and employees and bottom lines, you have to make money, otherwise it is not a business. But I felt that there had to be space for decisions driven by creativity and aesthetics, whether it makes money or not.’

Books are transportable, like a caravan home. There was also the matter, though, of creating a space for the books and stories that would not get published within traditional publishing. She wanted to provide a refuge for those.

And so Karavan Press was born, incorporating the K of her name, and the idea of transportability and shelter.

Small fortunes

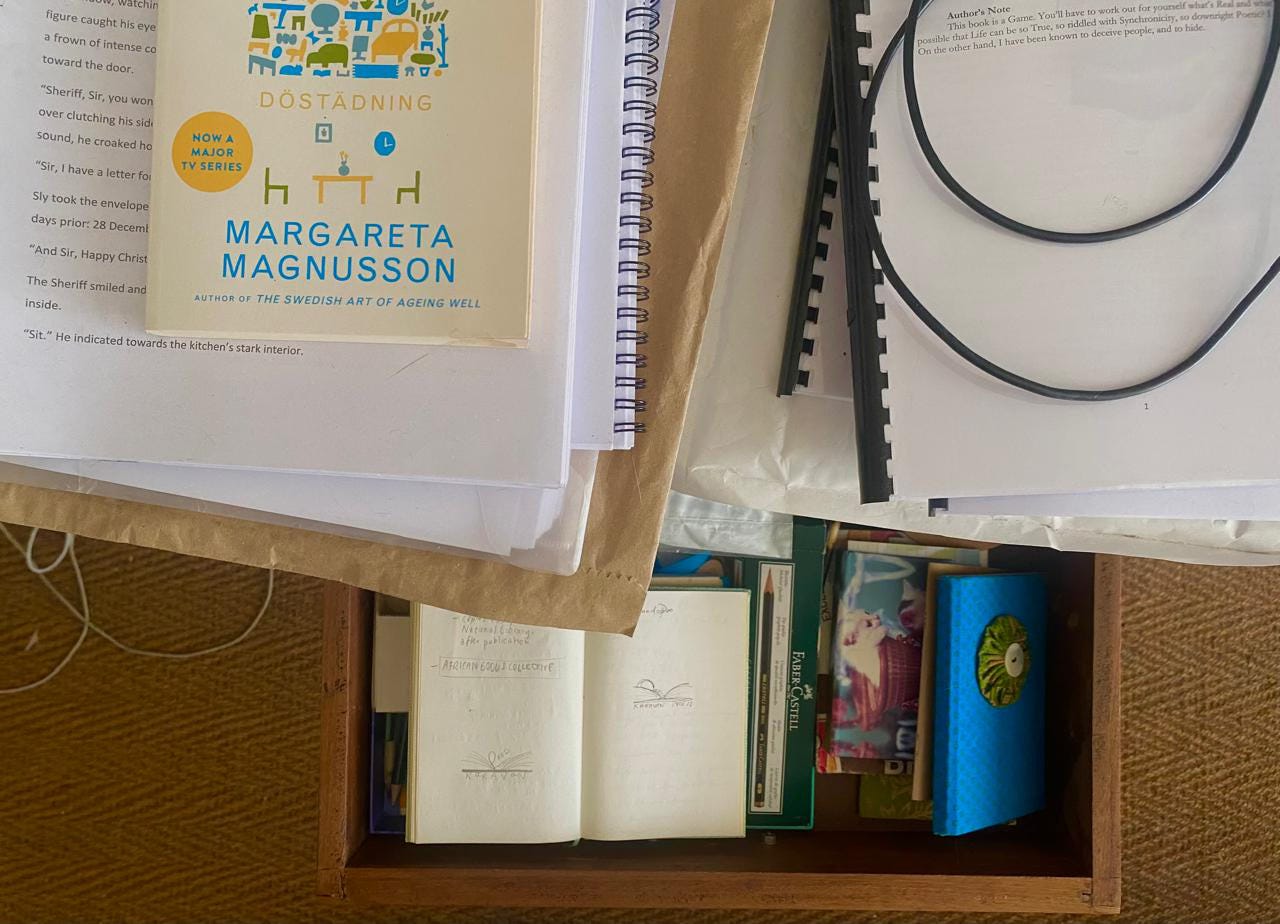

Apart from the work needed to be done by professional designers and by printers, Karina does everything at Karavan Press. She is all of Karavan Press: its hands, its brain, its editing, managing, arranging, marketing, author liaison. Financially, this was the only way she could make the project viable, because ‘to make a small fortune in publishing you need to start with a large fortune’.

What she didn’t know how to do she learned from Nick Mulgrew, owner of uHlanga. Over a few coffee meetings, she furiously wrote down everything he told her that he knew about publishing.

‘When the going gets tough, I go to the drawer where I keep that notebook and look at it, and I remember why I’m doing this.’

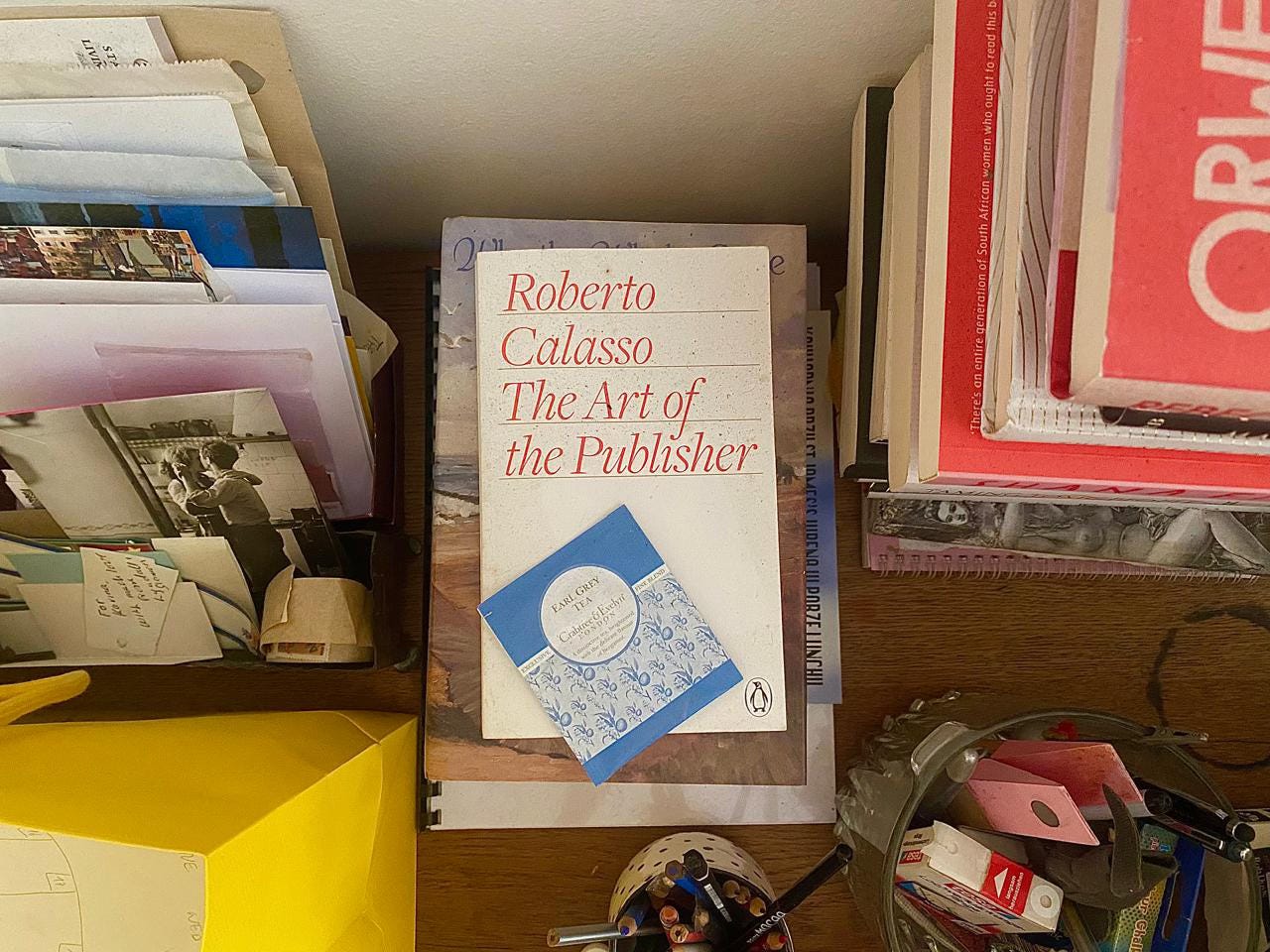

The book as object

About a year ago, I bumped into Bongani Kona, author, editor and current chair of PEN South Africa. He said, ‘Have you ever held a book made by Karavan Press? They are beautiful. Every book she publishes just feels so good in your hand. It’s such quality.’

How a book feels, and not just what it contains, is why Karavan Press only publishes its book in e-format when an author insists.

‘I never want to do it.’

Why not?

‘Because of Jeff Bezos and Amazon. And because that’s not why I went into publishing. I don’t want to produce content that is available outside of this object. The book as object is extremely important to me. So if someone had to say to me, from tomorrow, we can no longer print paper books, I would stop publishing.

‘A book is strong sensory experience that also translates to memory. When I read something on a screen, the chances of me remembering are reduced. My visual memory works differently when I start turning pages. When I read a physical book, the way I access the information in it is much more meaningful.

‘I can scribble in the margins, underline, highlight. I retain so much more, not only of knowledge, but also of beauty.

‘And I can always access a book. I don’t have to charge it. I don’t have to have electricity. I only need to rely on the book itself.

‘And I think maybe a lot of my past as a refugee child comes into play because for a long time I had no opportunity to form lasting relationships with people because we couldn’t settle anywhere. We were constantly moving. It was a constant barrage of loss of people, places, institutions. But what I could carry with me – books – they remained stable.’

Books, Karina says, are a palimpsest of writer, editor, publisher, reader. So when you hold the object in your hand you become aware that ‘this is not just you’.

‘And I love the way books look. They become furniture in your home in a way that an e-reader can’t. I feel safe and happy when I am surrounded not only by beautiful things, but exciting ideas.’

Tactility. Connection to things and to people. Constancy. Beauty. These come up often in conversation.

What does Karina look for when she decides to publish something?

‘I want to fall in love with the text. That’s it.’

Would you like to write an essay for Love Letter?

Love Letter’s having an essay competition this year.

I’m not telling you the date or how to enter yet, because those aren’t finalised. I just want to share this news for now so that you can start thinking about something you want to write that you think would fit in with the tone of Love Letter. Read past Letters here to get a sense of Love Letter’s vibe.

Here are some of the things I’ll be looking for:

I want to see through the author’s eyes and hear through their ears. I want authenticity, clarity, and a way for the reader to connect to the author’s experience. I have an aversion to cliché.

I like slice-of-life. I like small moments. I like realness. I do not like pretension.

Teach me something without lecturing me. Or teach me nothing, but make me marvel or make me smile. Surprise me.

I have a great capacity for sadness, but very little capacity for hopelessness.

I like scripts that arrive cared for and edited. It means the writer cares: about themselves, about their writing and, most especially, about the reader.

Here are some of the limitations to be aware of:

Word count = No more than 1 500 words.

Unless you offer (and I accept) an illustration, I will choose how to illustrate your essay.

If you win publication on Love Letter, I might suggest edits that are in line with my own preferred style guide.

Start writing and keep your eye on Love Letter, Instagram and Substack Notes for deadlines.

I look forward to reading your stories.

With love,

as always,

K.

I’ve just discovered I’m no longer being notified when you post here. Horror!

This was a beautiful profile - I especially loved the part about why she feels 100% at home in SA, because she’s given words to a feeling I’ve been unable to express. It’s the relative lack of homogeneity that enables weirdos like me to feel like we’re just maybe at the far end of society’s spectrum rather than outside it completely. I’ve never experienced that anywhere else.

Thank you Karin for such a beautiful Love Letter. For me the hardest thing in a move is the decision of which books to take. These guardians of my soul have travelled with me through countries, years and now with time drawing to a close I am parcelling up some treasures to give to both my children and grandchildren and particular friends who I know will exclaim with delight when they remove the wrapping and find what part of this wealth has been earmarked for them. They will recall when we sat together peering into and pondering what perhaps John Berger had to say on a particular painting or his thoughts on society and the way we operate in the system. Robert Macfarlane has guided my footsteps through wild places, his words have enlivened me, brought comfort in times of despair. There might be many advantages in this virtual world but to hold a book, open its cover, smell the print and the pages - that is something else.