There were issues. Any way you look at it, there were issues. They were serious and tenacious and they made my family different from my friends’ families. But there were always books.

My parents weren’t university students. Neither of them finished school. But there were always books.

We didn’t have a lot of money. But there were always books.

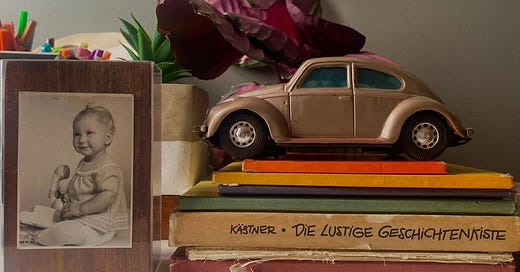

For the longest time, I was an only child. One night my mother read to me in Afrikaans; the next my father read to me in German. I often forget that I couldn’t speak English until I was seven.

The night before Grade 1, probably because I was tense about starting school the next day, I was upset when my mother stopped reading. I begged her to carry on and she said no, it was time to sleep, and I cried as though my best friend had moved away.

Drama queen.

I suppose the alternate reading nights must have stopped when I learned to read. I can’t remember the transition.

But there were always books.

There was the silent central city library where dust motes floated on beams of Highveld sunlight pouring in through high windows. The exact spot on the first floor where I found the book about the king who ordered the town to be painted one colour, then grew bored and demanded a new colour, until he came back around to everything being its own colour – I think I could find it now again. I can’t remember how my mother and I ever found one another again in that vast space, but next thing we’d be tootling back to the bus stop with our loot and that feeling you get from carrying home a new book.

There was a suburban library where I found a book about a sensitive loner of a teenager and understood all her achey feelings in my marrow. Whenever a suburban library is mentioned in a book, that’s the picture that comes up in my mind: a squat concrete block with floor to ceiling windows and two loungers in tobacco-coloured leather in the style of Mies van der Rohe. They stood at the front entrance by the notice board, and there were magazines on a glass table between them. I didn’t know anything about Mies van der Rohe, but the chairs were elegant and unlike anything I’d seen in anyone’s home, so they imprinted themselves.

There were always books.

There was no high-mindedness in Schimke reading. There were thrillers and courtroom dramas and Mills & Boons. There were stories of Georgian intrigue. Mythology. The Arabian Nights. European fairytales. Disney annuals. I was allowed to read comics if someone gave them to me, because we didn’t buy them. It was okay to go to the corner shop that smelled of deep-fried Russians and chips to flip through tacky photographic magazines in which girls with big hair and little bikinis were saved by blond men in bellbottoms and handlebar moustaches. I just wasn’t allowed to take my religious cousins there.

I read Princess Daisy in high school and got into trouble for reading trash. I’d been caught reading while walking in the corridors on the way to a new class, which was how my trash was discovered. I didn’t know that reading had tiers and that I was currently wallowing in a cesspool.

I paged through the Stern and Bunte magazines that came from Germany, and Huisgenoot and Fairlady printed in South Africa. For many years, I had a subscription to the oh-so-British children’s magazine called Bunty, a treat you cannot imagine the juiciness of.

Nothing was banned, that I know of, in our house. Our house was trash-reading heaven. We all read trash and often we’d catch something less trashy in our unfussy reading nets and there would be exclaiming and sharing.

There were always books for birthdays and books for Christmas.

There were always books.

When my appetite outgrew the home collection, I started to buy books from my wages from secondhand shops. Trash. Treasure. Trash trash trash. Treasure.

I am certain of very little in life. Very little. It’s all just guessing and hoping and dodging disaster mostly. But I have never, ever doubted that my parents’ best gift to me was reading aloud to me when I was little.

And I have never doubted for one second that an adult reading to a child is…I don’t know what is. I cannot find the superlative adjective required for this job.

Read to a child. Find a child. Borrow a child. Read to it. Read aloud. Read.

Fluit, fluit, my storie is uit*.

Love,

K.

*This was what my mother said when the book was finished. It means ‘whistle, whistle, my story is done’. But it rhymes.

Ah, this is a particularly wonderful Letter!

What a splendid childhood home you had … reading this brought back memories of my childhood, and yes, there were also always books. And we lived opposite a library, which was my second home, and where I first discovered that I loved English, even though I couldn’t understand a word. Didn’t stop me from reading book after book. My neighbour supplied trashy comics and KYK boekies. It was heaven. (And reading to my grandson is pure joy 🤍)