Today’s Love Letter is about the South African writer and artist Deon Maas, who now lives in Berlin.

Next week’s letter will launch the Love Letter essay competition for subscribers.

Here’s a reminder of what I’ll be looking for:

I want to see through the author’s eyes and hear through their ears. I want authenticity, clarity, and a way for the reader to connect to the author’s experience.

I have an aversion to cliché.

I like slice-of-life. I like small moments. I like realness. I do not like pretension.

Teach me something without lecturing me. Or teach me nothing, but make me marvel or make me smile. Surprise me.

I like scripts that arrive cared for and edited. It means the writer cares: about themselves, about their writing and, most especially, about the reader.

I look forward to reading submissions in July.

Enjoy today’s Love Letter.

K.

Dictators leading the way

‘He won’t show me what he’s doing,’ Veda Maas told me.

We were sitting at a table by the only window in a pokey Kneipe, an old-fashioned German pub where, somewhat quaintly, people stayed inside to smoke. Everyone peered at their tankards, and at each other, through a blue fog.

It was here that I remembered the old German tradition of knocking three times on the table in greeting. It felt like I’d come back to 1979, my second family visit to my father’s birth city.

But Veda and I were speaking Afrikaans, not German.

Language and home familiarity overrode strangeness. Beer softened boundaries.

Deon Maas, her husband, and I had spent the day traipsing around and Veda had joined us for a drink after work.

It emerged that Deon was ‘doing art’ in his ‘cave’ – the spacious room in an old block in a gritty, populous quarter of Berlin. He wasn’t showing it to anyone though.

‘It’s just for me,’ he said. ‘I’m doing it for me.’

It was April 2023.

Dictators

Not two months later, I was surprised by an invitation to the opening of an exhibition at which Deon’s collage art would be shown in Neukölln. It was for a group exhibition entitled Power/Play.

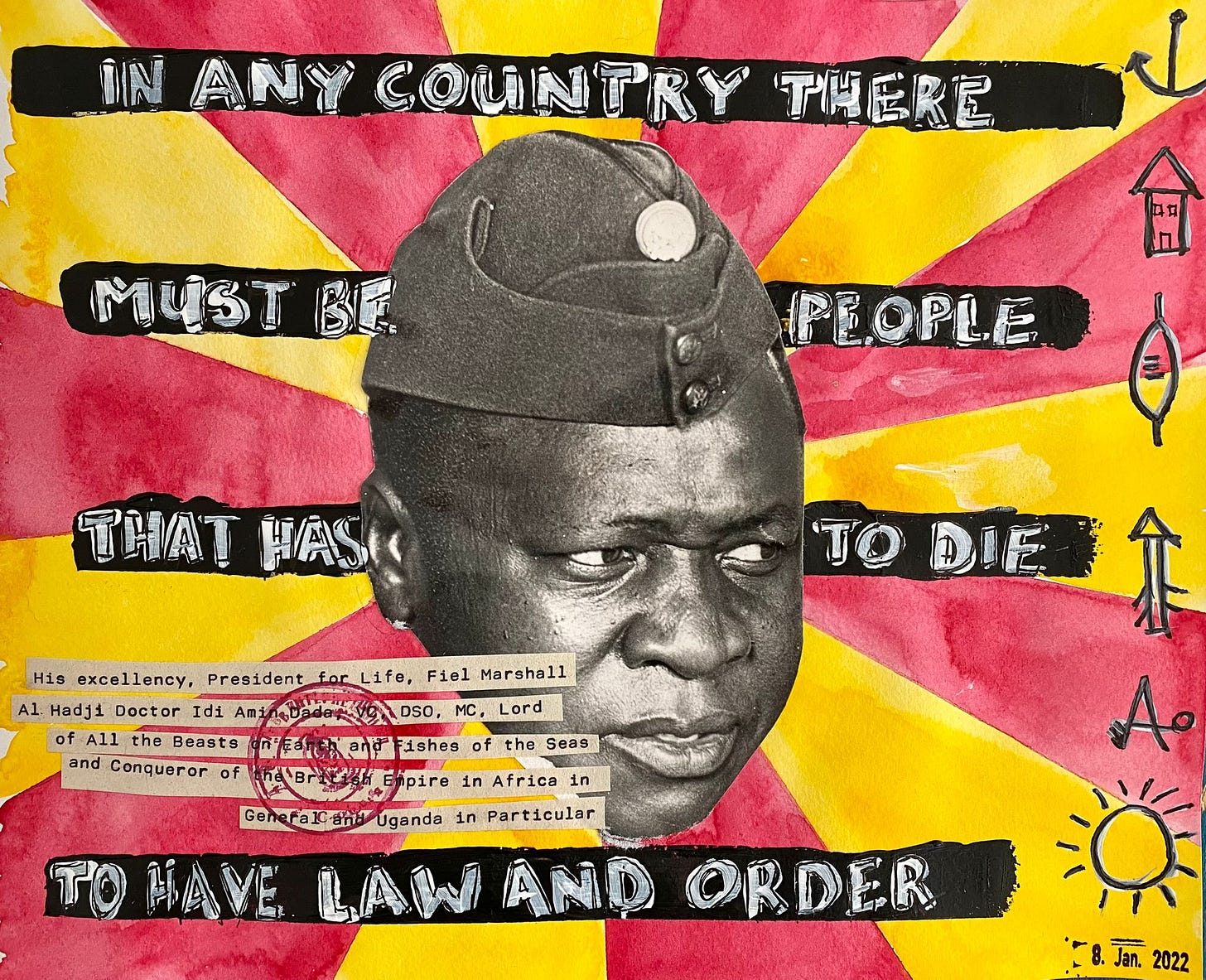

Deon focused (mostly) on dictators. The newsprint photographs of the deep-etched heads of Erich Honecker and Idi Amin, for instance, floated dead-centre against colourful backgrounds that included text.

It was a rather sudden turn around. Deon had seemed adamant that whatever art he was making, it was not in order to become an artist. In an Instagram post later that same year he wrote, ‘Ek noem dit nie kuns nie* - I find it so pretentious to see myself as an artist and all the snobbery and shit that comes with it.’

Old cows

Now, in June 2025, almost exactly two years after that exhibition, Deon has a solo exhibition in South Africa of new collage work called ‘Ou Koeie’. The exhibition’s title is a reference to an Afrikaans saying that, directly translated means, ‘Don’t go digging old cows out of ditches.’

It means ‘let bygones be bygones’.

On the day of the opening of his exhibition at the Breytenbach Centre, he sold just under half of the work on display.

In this series of collages, the faces planted bulls-eye on art paper and surrounded by the peculiar, silly and outrageous utterances from the mouths on those faces, are recognisable as people who were often – or memorably – in the news before and after the transition to South Africa’s democracy.

All the work has the slightly grubby, graffitied texture of a Berlin public surface, and it’s clear that the city’s abrasive, rebellious spirit has been absorbed into it. Deon’s love of history, his careful reading of politics, and his sensitivity to pop culture are all accounted for.

What they reveal is that the present is merely the most recent iteration of all that has gone before. That now is a decades-thick palimpsest. ‘This is built on that,’ his work says, ‘which is stuck on this, covered over by that event, which was influenced by the incident before that.’

History is a lot of new-on-old-on-new-on-old.

The present is merely the most recent iteration of all that has gone before.

How did he go from not showing his work (even to his wife) to a solo exhibition in two years?

Veda caught sight of one of Deon’s works by accident and said, ‘Maar hierdie is dan befok!’

It translates as ‘but this is be-fuck!’ – possibly the highest praise one can elicit in the Afrikaans language.

Deon then and now

I’d met Deon for the first time on the same day we met Veda at the Kneipe.

There were, as there almost always are, hundreds of people swirling around the World Clock on Alexanderplatz in Berlin where we’d agreed to meet, but Deon Maas was instantly recognisable.

His aesthetic has always to been iconoclastic, and culturally as far removed from his Afrikaner background as it is possible to be. Just by looking at him – his rings, his lobe gauges, his sleeve tattoos – you can see how he must have been a blow-out of a botheration for the Boere-mentality.

Yet he presents as neat and contained; stylish, though not styled. He exudes a sartorial punkish fuck-you-ness one seldom sees in South Africa.

His outsider status, when he lived here, might have been signalled by his decisions about dress, but in Berlin, he looks like an insider. On the chilly day we met by the historical clock, he looked, in fact, like he was Berlin-born. Not at all like a recent import from the continent of Africa.

We’d never met. I’d written about his book Witboy in Berlin before I travelled to Germany in 2023, which led to an invitation to do a walkabout with him when I got to the city. He’d arrived there in 2017 to follow Veda, who’d landed a cool job. He came with one suitcase full of clothes, a backpack with his laptop in it, and a satchel with his old notebooks.

He went from a man with the secure possessions – including a high public profile – of a mid-career professional, to sleeping on a blow-up mattress.

He got a good job working for a Swiss cannabis firm and, settled into a new rhythm of working and walking the dogs, he found he had a need to make visual sense of his past and present, and thus began making collage.

At a cavernous Cape Town eatery run by Gen Z’s in moustaches, beanies and dungarees hanging off just one hook, he explained how the work he wouldn’t show his wife had blossomed into something that had changed him in surprising ways.

He drinks less alcohol, he told me, and he hasn’t had a single road rage incident driving on Cape Town’s roads. Discovering, after the age of 60, the effect of working creatively with his hands happened almost by accident.

‘When I feel a bit anxious or worked up, it’s literally ten or twenty minutes on this art stuff and I’m totally Zen again.’

His unexpected success doesn’t mean he isn’t still doing the work only for himself. When he realised people would pay for his collages, he promised himself that he would not be tempted to make what people wanted, and to keep creating what gave him pleasure.

For the first time in his life, he is not weighing up the financial outcome of his interest. Veda earns enough to support them both and he lives small. He owns three pairs of jeans and three pairs of takkies*, he says.

The bonfire

Deon started off as a journalist and had a varied career in writing, film and documentary making. He wrote a weekly column for the Afrikaans Sunday newspaper Rapport, pissing people off left, right and centre. Most visibly, he was a judge on Afrikaans Idols.

But all the demands of being the person he was in South Africa – someone with a certain fame – or infamy – and a recognisable face fell away when they moved to Berlin.

‘It weighed heavily on my shoulders,’ he says about his life before Berlin. ‘It was very uncomfortable. I never liked it. I’d always been behind famous people and suddenly, in my mid-forties, I find I’m on the front page of newspapers.’

Worst of all, being on the front page of newspapers was what was paying the rent. Deon’s columns in Rapport made him one of the most reviled Afrikaners for a while. Not because he was trying to be provocative, but because his opinions naturally run against the grain.

‘This controversy I created without even trying had turned into my life blood. This was how I made my money.’

Which might sound like a strategy of sorts, but was the outcome of being naturally mutinous.

As they prepared to move to Berlin for Veda’s work, the couple sold everything they had in order to finance taking their dogs with them. With what was leftover of Deon’s possessions, he made a bonfire in the back garden and sat through the night feeding it while drinking a bottle of Laphroaig.

‘Bonfire of the Vanities,’ I say, referencing the famous 1987 novel by Tom Wolfe.

‘Exactly. A bonfire to my vanities,’ he confirms.

Balanced

At the opening of his solo exhibition at the Breytenbach centre in Wellington, he jokingly responded to a question about being anti-establishment – anti-everything – by saying, ‘How can anyone be pro anything?’

I asked him whether there was any word that best described his political and social nonconformism. Is he an anarchist, a nihilist, a socialist, an atheist, a heretic, a libertarian, a pessimist? What word best described him, I wanted to know.

He sat back and finished chewing a bite of his slice of lemon drizzle cake, iced with frosting as white as his mullet, and said the thing I least expected.

‘I’m balanced.’

I laughed. Of course a text-book heretic is not going to have an obvious label for themselves.

‘I have never belonged to any organisation. To belong to an organisation is to have to make compromises. You have to buy into the belief of the organisation, whether it’s Christianity or the ANC. That’s why I’m not pro-anything.

‘Everything,’ he says this with emphasis, ‘everything, is open for criticism. Everything must be questioned. No system is perfect.’

Before I met Deon, I imagined him to be a lot like almost every other male journalist I’ve ever worked with: showily cynical, sure of himself down to the least matter, and eager to preen, inform and regale.

Instead, I experience him as opinionated, but thoughtful; quiet but never shy to point out when someone is talking nonsense. He is unflinching in the face of fallacy and hashed facts, but he is not antagonistic or pugilistic. Or perhaps he is, and I’ve just not seen him that way.

He is also twitchily curious, restless, and hungry for newness. As a free-range (and an unknown) citizen of a city that never sleeps, he has found a new kind of belonging, one that suits a person who likes to be alone, watching, seeing, thinking.

Eight years into life in Berlin, he still wanders the streets, a collector of images and ideas. It’s no surprise, really, that all this soaking up must produce something, and that what it produces is art informed by street culture.

At some point in our conversation this week, Deon said to me, ‘We,’ (meaning he and I), ‘have overlapping philosophies.’

Only later did I ask him, via WhatsApp, what he meant by that.

‘My philosophy is there is only one commandment. Don’t be a doos.’

Translations

*’Ek noem dit nie kuns nie’ means ‘I don’t call it art.’

*takkies is the South African word for sneakers.

If you enjoyed reading this, please share Love Letter with your friends and colleagues.

With love,

as always,

K.

This description, of art and man, is gem - a work of art in itself, as your writing tends to be. Deon is blessed to have you words about about him. His art looks thought provoking. I didn't know that expression about old cows fallen into dongas being equivalent to bygones - it's awful to think of them just left there.....