On a still, warm morning before the new university terms started this year, I pulled up outside a house almost completely obscured by the greens of a forest-like garden. The house itself was green. Its owner came to greet me wearing a green shirt. She took me through to a green kitchen that had double doors leading out to the cool-looking green of a back garden.

I was there because not long before, the first time we’d met in person, she’d drawn an imaginary rectangle with her pointer fingers and said, ‘I like the constraint of the rectangle.’

The rectangle she is referring to is the shape of a book. But I soon realise that a rectangle could any restraint or limitation.

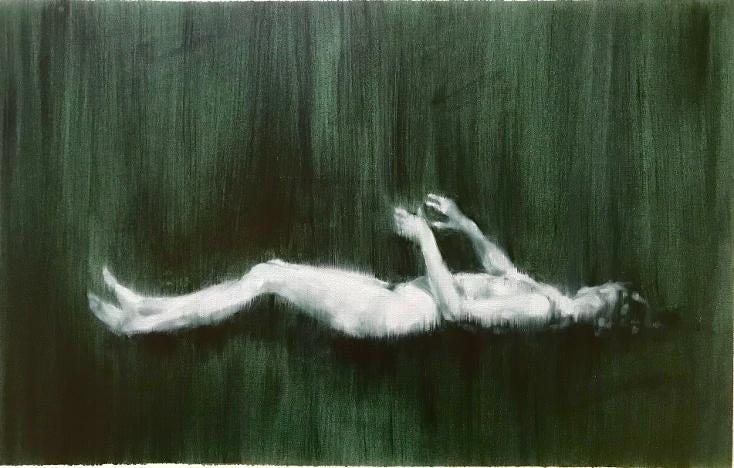

Gretchen van der Byl is an artist. Her slightly blurry paintings always suggest dreams and memories to me: intimate, private images surfacing from the unconscious. But is it my unconscious or the artist’s? Are the images part of the collective unconscious that lives in us, or one individual’s? Didn’t I dream something just like this:

or like this?

Curiosity as ethics

I came to know about Van der Byl because every now and again, I’d pick up a South African book – like one of Simphiwe Gloria Ndlovu’s, or Hedley Twidle’s collection of essays, Show me the Place, or Ivan Vladislavić’s The Distance – and admire the cover enough to open it up and see who had designed it. It was almost always Gretchen.

We are meeting to talk about book cover design, but the kettle has hardly boiled and we’re in territory much deeper than covers and surfaces.

‘You can’t have empathy if you’re not curious about someone else’s experience,’ she says, as she gets the cups and tends to the coffee.

‘And you can’t have compassion without curiosity, and you can’t have discovery, and you can’t have resilience. Curiosity is a gateway to so many of the ways that we have to be in the world. It’s a door. It’s a threshold that you have to step over. And you have to bring curiosity to everything you feel internally, so that you can reflect on whatever you think’s caused that internal state.’

Curiosity, she believes, is an ethical way to proceed through the world.

‘How is one ethical in the world? That’s a question we have to face every day when we’re inundated with the state of the world. How do we respond ethically? How does one think about the world ethically and make work that doesn’t perpetuate or condone or add harm?

‘Curiosity is important for that. It’s a lens that you can turn on everything. You can even turn it on yourself. You can bring curiosity to uncomfortable feelings and it kind of makes the feeling go away. You’re so busy being curious about the thing, that the discomfort is not accessible because the curiosity has taken over.

‘Curiosity immediately puts you in the position of the watcher and the observer, which is what one needs to allow the feeling to exist, not to make it go away. You allow it to exist, and then you allow it flow away on its own timeline.’

The meandering route to the frame

We took the long route to book cover design. ‘Talking about book-cover design’ turned out, in fact, to be the ‘constraint of the rectangle’ of our conversation, which ranged and tangled over a wide field of topics.

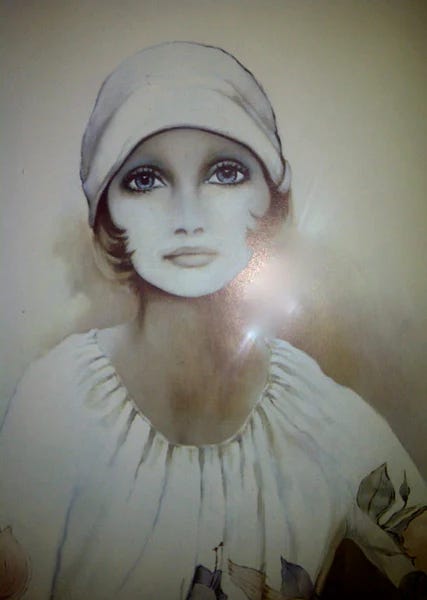

She showed me the book that changed the way she felt about the interaction between word and image (I wrote about it here) and told me that her childhood home wasn’t full of art, but that her mother did have some Sara Moon pictures.

We spoke about distinctions in art and literature, the divisions between, ‘worthy and unworthy, and high and low, and crap and trash’. I said something about wishing that a certain book chain in South Africa had chosen to call itself ‘Inclusive Books’ instead of its opposite.

I apologised for going off on a tangent.

'I like tangents,’ Van der Byl responded.

‘Ja, me too,’ the transcript tells me I said.

About book covers though…

Van der Byl sees her responsibility as a book-cover designer as being to the author and to the script she has been tasked with illustrating. She takes an enormous amount of information from the writing and condenses it on to the cover rectangle. This design will represent the tone, the themes and the head movie that unfolds in the magic that happens when a reader’s eyes passes over a collection of words.

She herself judges books by their covers.

‘I think we all do. If a cover is glossy or moulded or embossed, then, mostly, no thank you. And if something’s been indifferently designed…well, you’re asking me to care for the content and I find that dissonance hard to overcome. It’s difficult for me to buy a book that has a cover I don’t respond to.’

She believes readers could be given more credit for their aesthetic sensibilities and that book-cover design benefits from not pandering to fashion.

We keep returning to frames and framing

We spoke about frames in relation to the way in which we make meaning from events and images and synchronicities. If we didn’t find patterns and reasons and links we’d be ‘living like accountants with a ledger book’, she said. Our lives would be just one thing after another. Making meaning was ‘the binding matter, the sinew’.

It is also a frame.

‘It’s a delimitation. It’s a corralling of something small that then becomes meaningful and potent, because when there’s everything then there is nothing.

‘I get to rebel against the rectangle, and sometimes I get to embrace it and treat it as something to push gently up against and see what happens in a space that is intensified because of its scale. Because it’s so small, it’s naturally concentrated. Your vision narrows down. And you could go, “how frustrating” or you could go, “twhat opportunities are coming through this telescope?”

We should ask of the limitations imposed on us, whether in art, or life, or book-cover design, ‘What can we do with the intensity that’s built into this?’

When there’s everything then there is nothing.

She spoke about the intentionality of every choice made for the cover of a book.

There is intentionality in curiosity too, or certainly in the kind that Gretchen is talking about. To decide to be curious – especially when curiosity wanes as responsibility, weariness and the heaviness of the world grow as we become our adult selves – is not only linked to ethics, but also to rebellion. To an intention to live under the surface and not on it.

Why is intentionality important?

‘Because ideas accrete into masses that then sustain themselves just by their own weight, like a perpetual rolling on and on and on. At every moment, the task is to recognise how often you have choices within the frame you are given.

‘Otherwise, you are just rolling along with that rock.

‘There is so much in this world that is handed to us as a truth, as a thing that is. The space for agency is so limited, we’re going to take it wherever we can. So whether you’re making a little painting, or making a big sculpture, or whatever you’re doing, you need to be intentional about every choice you make, so that the thing you make asserts itself differently in the world.’

I ask her about the green, so abundantly in evidence in her home. She seems surprised when I point out there’s a lot of green around her, but concedes that she does love the colour.

‘It’s the colour of possibility, I suppose.’

Love Letter changes

I mentioned last week that Love Letter is turning three and things will be changing a little.

Paid subscribers enable the continued existence of Love Letter, which takes at least one day of work a week, sometimes more.

From March, paid subscribers will have the following benefits added to their subscriptions:

Two (instead of just one) exclusive Love Letters per month

Discounts on manuscript assessments throughout the year (see here for more information on manuscript reviews and other services)

My reading, poetry, music and viewing recommendations for the month

Access to my playlists

One Love Letter per month containing special offers on my writing and coaching services

Discounts on workshops

An invitation to take part in a Love Letter essay competition.

Founding subscribers – those that pay a once-off sum more than the annual subscription – have all these same benefits, plus the annual invitation to January Reset, which this year included a free one-hour thinking session with me in 2025.

They also have invitations to exclusive catch-ups and other special events in the year.

Two women, two very different speeches

Listen to Tilda Swinton’s acceptance speech when she is honoured with the Golden Bear at the Berlinale 2025. It is full of things that people might only be able to hear from highly talented, famous and very visible people.

Listen to the speech, also in Berlin, by Francesca Albanese, who is often shut down and denigrated for being the bringer of facts to an explosive political discussion.

Both women are powerhouses, admirable in their courage, their expertise and their ability to communicate clearly. Admirable in their curiosity and their ethical stance.

The world is going to need more and more of its movie icons and famous people to speak truth to power in coming months and years (like Tilda Swinton did) because great swathes of the populations across the world do not want to listen to the people (like Francesca Albanese) who are on the ground gathering facts instead of thumb-sucking nonsense to inflame hatred.

Goodbye until next Friday,

with love, as always,

K.

So glad this hit a note for you today, Noah. Gretchen is wonderful to talk to. And I so admire her work.

Such a gift to read as I start my Saturday, thank Karin. Your art of interviewing and writing them into stories that take us intimately along with you, is exquisite